One Sunday, I took trains and buses up to Boulder, Colorado to look around. As usual, my trip started at Arapahoe at Village Center Station, but that was unremarkable (except very early for me. My body was protesting). The adventure really started here:

in the underground bus terminal at Union Station in Denver. When the original sewers were decommissioned, this part was repurposed for waiting bus patrons. Just about all subsets of humanity (and several subsets of canininity) come through here eventually, so it's a great place to people watch. But there are guards everywhere and they don't want you sitting on the floor.

I waited about an hour for the Flatiron Flier to Boulder. This is a good route to view the high plains north of Denver. This is mesa country. Sometimes (like driving across Kansas) it's difficult to tell that the plains aren't really flat but it's pretty obvious here where hills like Lake Mesa and Davidson Mass provide plenty of contour. It's all fairly new (less than 2 million years old) sediments washed out of the mountains. Some of the older stuff, called the Laramie formation, around 100 million years old, has been mined for coal near Superior, Colorado. Keep in mind that the Laramie Orogeny, the mountain building event that created the current Rockies, happened between 80 and 35 million years ago. Coal forms from lowland plants in marshy areas. Colorado was low and wet back then. I've spent some time wandering around out there (Wednesday, June 21, 2017, Flatirons Crossing).

I disembarked the bus at Euclid and Broadway, right in front of the Henderson Museum. Just about anywhere in Boulder that trees or buildings don't block the view is a good place to see the Flatirons, named for their resemblance to the domestic contraption.

They are, in fact, part of the same formation that includes Red Rocks Amphitheater near Denver and the Garden of the Gods in Colorado Springs.

The eastern facade of the Rocky Mountains is well ordered in Colorado. It springs abruptly from the plains and can be seen a hundred miles to the east. It was an imposing and dreadful site to the early pioneers trying for California.

The foothills: Green Mountain, the Table Mountains near Golden, mesas and Mount Carbon, are just stuff that washed out of the rising Rockies (with a few older layers surfacing). The actual wall begins with the (still sedimentary) Dakota hogback. Then the Fountain formation covers the first of the Rockies like a blanket. Then the actual mountains of the Front Range soar skyward.

The Fountain formation used to be horizontal, flat. It was sand laid down by an inland sea between 290 and 340 million years ago, what geologists call the Pennsylvanian age. It was at the edge of the new Rocky Mountains when they were uplifted so they were cracked open and tilted skyward and that is exactly how the slabs of sandstone called "the Flatirons" appear. I'm reminded of the scenes in the movie 2012 as California folded up and toppled into the sea.

But that doesn't seem to be how it was. Judging by studies of stream erosion and other means, the Rockies seemed to be uplifted in three steps, each very slow by human standards. The initial uplift happened between 80 and 50 million years ago. The land rose about a kilometer at the rate of about three hundredths of a millimeter per year...hardly breathtaking. The second stage began about 35 million years ago and continued for about 20 million years. That brought the Rockies up another kilometer and a half at a breakneck speed of six hundredths of a millimeter per year. The last phase of uplift began about five million years ago and is still going on. Come to Colorado and watch the mountains grow! (Heh) This data is from a study published by G. G. Roberts, N. J. White, G. L. Martin-Brandis, and A. G. Crosby entitled "An uplift history of the Colorado Plateau and its surroundings from inverse modeling of longitudinal river profiles" (August 16, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012TC003107)

Most of the rocks of the Fountain formation are red, gray, or black. The color is from iron that was in the sediments. It rusted, like iron does.

I checked my altitude by GPS at the bus stop in Boulder. It was 1611.44 meters (that's 5287 feet, roughly a mile.) I am gratified at how much better I feel at this height than when I first visited the Denver area.

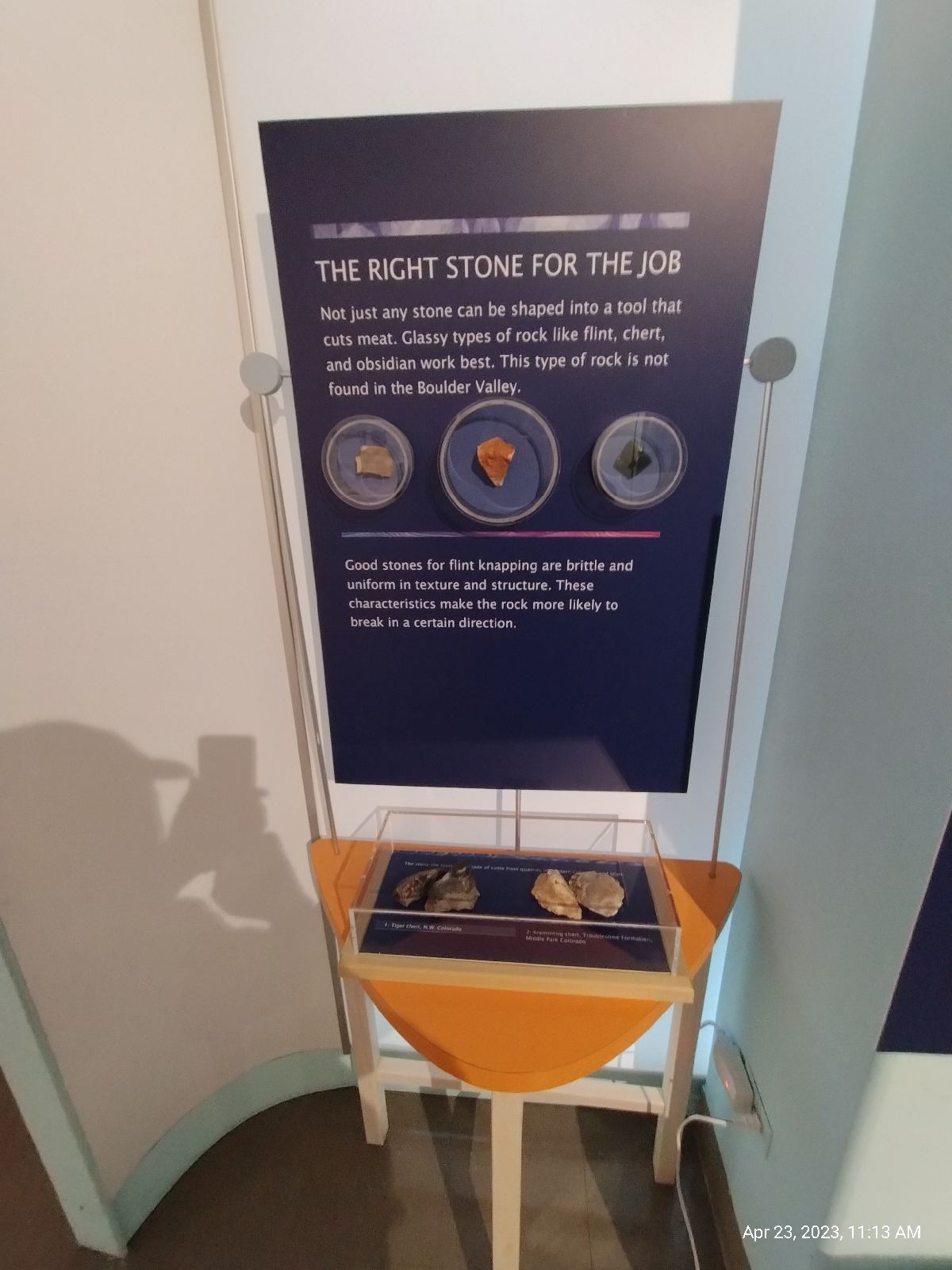

The Henderson Museum, the University of Colorado's museum of natural history, is a small affair with four rooms of exhibits, some permanent, some changes over time since it is an educational museum with students learning to curate.

There is no admission fee (they do appreciate donations) and there is a lounge with vending machines and places to sit and rest and make notes. One of the permanent collections (shown above) shows mostly local fossils, a wide range of plant, invertebrate, dinosaur, and mammal species. There's also a lot of cultural and historical exhibits, as well as current and historical science.

The building, like many of the cyclopean structures on the University of Colorado campus, is constructed of Lyons sandstone quarried nearby. The material was deposited by an inland sea around 250 million years ago. It's a very tough, fine grained, pretty stone that occurs in horizontal layers that are easy to quarry. See?

After a bite and a milkshake, I caught the NB2 bus up Boulder Creek Canyon to Boulder Falls. I figure NB stands for "Nederland bus" since it runs between Boulder and Nederland, Colorado. (Eh. It might stand for Nederland Boulder. Who knows?)

The Stony heart of the mountains is disclosed here. Boulder Creek has cut right down through it. I took another altimeter reading and found that I was about 2200 meters (7218 feet or about 1.4 miles) above sea level. That's 589 meters (1932 feet) above Boulder.

The elevation up there is 7886 feet (according to the topographic map on the AllTrails app.) The creek has cut 668 feet through hard granite. (More actually since "up there" has been worn down considerably over the millennia and the creek was another 20 feet below me.)

The oldest rock in Colorado is a 2.5 billion years old mass of quartzite in the northwestern corner of the state. Colorado was beachfront property near the equator when an arc of volcanic islands crashed into it piling up debris like a pileup on a California turnpike. Later collisions added landmass to what geologists call the "Wyoming Province". This early formed piece of crust, called a craton (Greek for "shield") formed a permanent part of the North American tectonic plate.

About 1.7 billion years ago, a second collision to the south caused widespread melting in the crust that hardened to form the Routt Plutonic Suite, the early core of what would be the Rocky Mountains. That's what one sees here in the Boulder Creek Canyon. Technically, the rock isn't granite. It's granodiorite, but I can't tell the difference. Granite has potassium (orthoclase or microcline) feldspar and granodiorite has sodium (plagioclase or andesite) feldspar. The only way to tell the difference is by thin section microscopy or chemical analysis, neither of which I have access to. But granitic, it definitely is. The photo above shows the white grains of quartz and white and pink feldspar and the dark hornblende clearly. Some of the dark grains are biotite mica.

All the granite is broken into big blocks. It was buried for millennia under thousands of feet of sediments. When the pressure came off through erosion, the rock expanded like a spring and cracked. Water seeped into the cracks and, by repeated freezing and thawing, expanding and melting, wedged the cracks further apart. Eventually, it all goes down into the creek to be washed to the Platte River, then the Mississippi down to the Gulf of Mexico. Chunks of granite erode to rough spheres, thus, "boulders".

The rocks are grainy because they solidified far underground from vast bodies of molten magma where they had plenty of time to form crystals. Molten rock that's ejected onto the surface of the Earth as lava cool quickly and present either a fine grained or glassy texture. I saw several pockets of large crystals of feldspar in the rock walls. The minerals fall out of melt in a definite order and, when they get a chance, will clump together like that. Quartz is the last to solidify. It usually forms the matrix in these grainy igneous rocks.

The rocks in Boulder Canyon are crosscut by numerous faults, veins and dikes. The faults are where large bodies of rock have broken and slide against each other.

Cracks in the rocks serve as conduits for mineral rich waters under high temperature and pressure. They deposit their mineral loads into the cracks to form veins.

Molten rock flowed into cracks, pushing the solid granite apart and hardening to form dikes of different igneous rock.

Granite carries mica that gives it a flaky texture and when it expands as pressure is taken off by erosion, it sheers off big curved sheets. The process is called "spalling" and it's evident in several places in the canyon.

I didn't really expect much from Boulder Falls. The photographs I've seen portray it as not much more than a cascade. The photographs don't do it justice

I tried. I think the problem is that the surrounding canyon walls just dwarf the 70 foot torrent from the slot canyon. It's a respectable cataract.

It's also popular so, if you visit, prepare for people watching. The falls are visible from the road. It's a very short hike (with stone steps in the canyon wall and handrails where needed.)

I'm a fanatic for waterfalls, so I think I'll devote a whole blog to them soon.

Having satisfied myself that the bus trip to Boulder Falls was well worth the time and effort, I waited for NB1 on its return route from Nederland and rode as far as Fourmile Canyon. I wanted to do at least a little footwork.

The Boulder Creek Path runs through the last few miles of Boulder Canyon before it opens out directly into Boulder, Colorado at Eben G. Fine Park. There are signs of human construction there that were probably erased in the big flood of 2013 which destroyed...well, a lot.

The creek gives. It's pretty much why Boulder was established February 10, 1859...gold, of course. And the creek takes away. 2013 wasn't the only disastrous flood ever to roar out of Boulder Canyon. I was in Selma, Alabama at the time but my current family was already in nearby Broomfield, so I watched the news closely. It turned out that they were in no danger.

But the creek has taken a lot more than construction. The front wall of the Rockies...the hogback and Fountain formation have been all but obliterated along the Creek's path. There is a brief area of Dakota sandstone just before the mouth of the canyon. It's not enough to call a hogback.

See the deer?

There is a lot of wildlife in the canyon but this is all I spotted on this Sunday.

There are a few vestiges of the Fountain formation in Red Rocks Park across the creek from Eben Fine.

These are the same kinds of rock sculptures as those in Red Rocks Park in Morrison, Roxborough Park near Littleton, or the Garden of the Gods in Colorado Springs. In fact, there are "red rock" formations that extend through Wyoming and Colorado. If they are a sedimentary blanket that was pushed up by the Colorado uplift, do they appear in areas other than the eastern margin of the Rockies?

Indeed they do. They form huge rock sculptures near Woodland, Colorado, west of Pikes Peak.

And also show up on the western slopes as the Maroon Bells.

After a grueling hike up "The Hill" in search of a Flatirons Flier bus stop, I took a long (and welcomed) bus/train ride back home.

I started this blog with inconceivably long periods of time. I guess I should add some caveats and explanations here.

People talk about "Big History", that is, the history of everything from the beginning of the universe to the end and all the reality forming, universe shaking events between. I'm bothered by the term "history" here. In my view, history is "what happened". If it's history, then someone experienced it and recorded it. We have no records of experiences from millions and billions of years ago.

So, why would I say that the Laramie formation is one hundred million years old?

Best guess.

Based on what we know about how the world works, the most cohesive view of "Big History" involves millions of years and lots of trial and error by nature. One way that we have of "knowing" is time measurements by measuring the amount of radioactive elements in an object. For rocks, it's usually uranium or thorium. The isotopes we look at decay so slowly that there will always be some around. But we do know how fast they decay, we know what they change into, and we're pretty sure that we haven't lost or gained any from the beginning. Uranium and thorium are far too heavy for us to lose into space and the amount found in rocks is trapped there. If we gain these heavy elements, say, in meteorites, well, that would mean that the rocks are even older.

Keep in mind that it's not the amount of elements in the rocks that we look at, it's the ratio of their concentration to the concentration of the elements they decay to...or I should say "element" since most of them decay to lead. So once a rock forms, it has the amount of radioactive material it will have trapped in it. As time goes on, the radioactive element decays at a fixed rate. Today, we can check to see how much, say, uranium there is in the rock compared to the amount of lead, and we can calculate the time since it formed.

How old are the rocks in your area. Some people are surprised to find that the Appalachian Mountains in eastern North America are much older than the Rockies. You can learn a lot about your geology from geologic maps of your area. I use an app called Rockd (by Macrostrat Labs at the University of Wisconsin - Madison) to pull up geologic maps and information about local geology in many places worldwide.

No comments:

Post a Comment