"I don't know.

I don't know.

I don't know where I'm a gonna go

When the volcano blows."

Charles Thompson, Violet Clarke. Volcano. Sung by Jimmy Buffett, 1979.

Well this volcano won't be blowing it's top. It's been dead for 60 something million years, but it's still interesting so I went to check it out and found more questions.

Golden is more than a day's outing. There's a lot(!) to see and do there. My goal was to visit the geology museum, then take a look at the lava flows on North Table Mountain, and finally to hike out to the actual volcano, but questions intruded so this blog will be continued at a later date. First, an introduction to the area...

A good place for an overview is the Jefferson County Government Center. It's the first thing you see when you get off the train on the W Line and it sits on a hill overlooking the town (remember that if you're on foot. You'll have to come back here if you take the train back home.) You see all the mountains surrounding Golden, Golden itself, and Clear Creek Canyon in which the town is nestled. The university, the golf course, the tourist attractions... they're all down there. And the lava flows, North and South Table Mountain are to the right in the photograph above. The actual volcano is some where to the northwest. It turns out, I don't know where. It might be that hill in the left background with a white streak going up and around it. On Google Maps and Rockd, it's called Rolston Dike. There is also a spot on North Table Mountain that has been proposed as the vent. Then there's another dike between Golden and Boulder that might be the actual volcano. I'll be checking out Rolston Dike on a later hike.

The Denver area was once beachfront property (Actually, it's been beachfront property several times in the past.) When the sand that formed this rock was deposited by an inland sea, it was near the equator. You probably would have loved it. You could sit on your patio and watch the triceratops graze in you back forty.

The first triceratops skull in Colorado was found here. It now resides in the Denver Museum of Science and Natural History. Almost all the fossils found in the area (and there have been many!) have been found in this stuff.

I would imagine this is Dakota sandstone, the same stuff you see on Dinosaur Ridge. You won't see a hogback here in Golden, though. Clear Creek has pretty much obliterated it. You might wonder how such a little bitty creek could do so much damage. Of course, if you lived here long enough to have seen some of the past flash floods, you might not, but that's not the answer.

Did I mention that Colorado used to be near the equator? Climate has changed and when Clear Creek started carving out this part of the Rockies, there was a lot more water and it was a roaring river.

It's a tradition around here. Hikers leave their marks by adding to these little stacks of stone. If you hike in Colorado, you will see them at the side of trails or in the middle of streams. Of course, cairns have been around for as long as humans have been around, for instance, as boundary markers or memorials, but they're not a constant part of the human landscape. I didn't see them much in the southeastern United States. I suspect that, once one person starts a stack, others join in.

Lookout Mountain (left) and Mount Galbraith (right)

Over there, there are those huge masses of crystalline igneous and metamorphic rock, over here it's a lot of sedimentary stuff. That usually means that there's a fault somewhere around. You can't see the one that runs along the mountain front. It's covered up by a lot of debris, but it's there and it's big. When the Rocky Mountains rose, it pushed the rock from the west up and over the rocks to the east. How do we know?

Well, we can drill down to the different layers of rock and see which layers match. We not only know that it happened...we even now how much it happened!

The Golden fault parallels highway 6 in Golden about a city block west. It pushed the very old rocks to the west about 14,000 feet up and about a mile and a half east up and over the younger rocks of the plains. Mind you, it didn't happen overnight, but with all that slippage, something had to break and that would explain the volcanic activity here, and near Colorado Springs, and in the San Juan mountains of southern Colorado (which are almost all volcanic), and other places in Colorado.

School of Mines visitor center.

It doesn't sound like much, "School of Mines", but I realized when I was a tutor, that the Golden School of Mines is a prestigious university with tough entrance requirements. They are leading edge, for instance, beginning the first graduate program in space resources in 2018. Although they do offer minors in arts degrees, all the majors are STEM subjects and economics.

I always enjoy college campuses. They are usually sprawling museums and offer programs for the surrounding communities. Mines isn't different. The grounds is peppered with numerous statues.

The architecture is always fun to look at. Check out the pilasters on this building.

The building across from the geology museum, the Steinhauer Field House, is especially ornamented.

It was a Sunday, so the museum was only open from 1:00 to 4:00 pm. I had plenty of time to wonder around Golden before then.

Just down the street from the museum, Clear Creek is already a respectable stream. Of course, Clear Creek, the same Clear Creek I visited on the G Line, is many of the reasons for Golden. Geographically, the stream provided the canyon that Golden resides in. It is also what drew prospectors to this part of the country (the name "Rolston" is as prominent here as in Arvada) and Golden in particular. I made it a point to collect some material from the stream bed to look at. And when big industries came to Golden, they crowded around to creek for water and the train lines that developed nearby. Clear Creek also provides for tourists by offering trails and water sports like fishing and kayaking.

The Golden History Museum, on both banks of Clear Creek in downtown Golden, provides glimpses into the early life of Golden including this preserved slice of Golden from the latter part of the 1800s.

Notice the sign on the fence warning visitors that the bee hives are real and stingy.

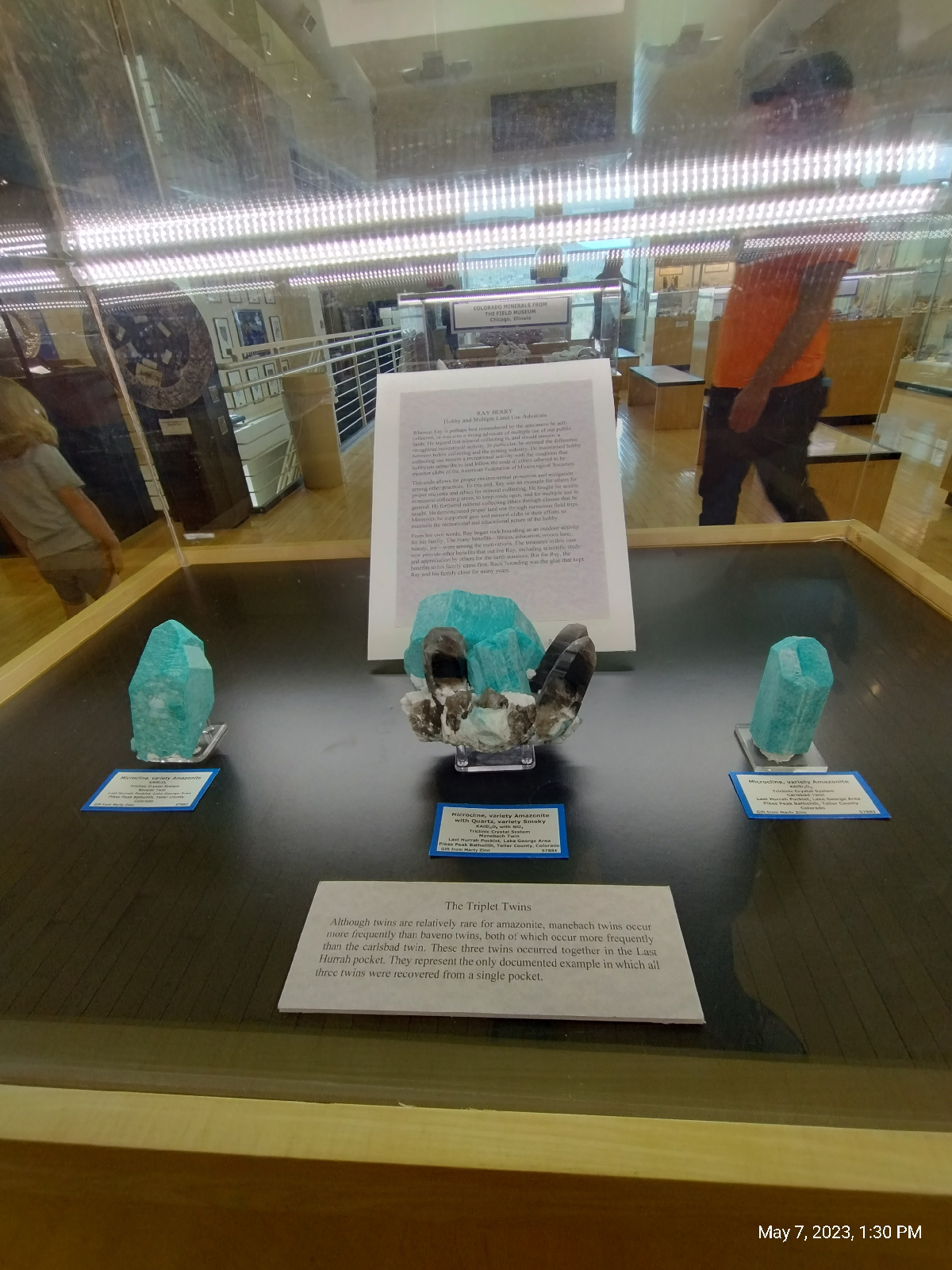

The museum is housed in a large building with many thousands of items, but the public display is in a single room. It's mostly a big (but breathtaking) mineral collection, but it does show a collection of antique instruments.

The minerals are from around the world (organized by region)...

Colorado...

and, more to the point of this blog, Golden.

Zeolites from North Table Mountain.

Zeolites are moderately rare in nature but are so useful that they have been manufactured in a great variety. They're useful because the aluminum silicate molecules have an open ring structure that's called "microscopically porous." By adding other elements and changing the conditions under which the crystals form, the size of the spaces between atoms and the charges on the molecules can be custom made for different purposes. Microfilters and ion-exchange materials are often made of zeolites, but there are many other uses.

In nature, there are a handful of different zeolites. The above specimens were collected on the Table Mountain lava flows above Golden. These are huge compared to the typical specimen, such as the one below that I photographed on North Table Mountain.

There are three lava flows on North Table mountain and two on South Table Mountain. The zeolites occur in the second flow as a white filling in bubbles (called "vesicles") in the basalt. They form as alkaline ground water percolates through the basalt and precipitates dissolved materials into the bubbles.

After drooling over the gorgeous specimens in the museum, I headed back to Clear Creek, and made my way to the flank of North Table Mountain, a grueling hike up steep residential streets.

View from North Table Mountain

Lookout Mountain to the right

South Table Mountain to the left

South Table Mountain (that's Castle Rock at right center)

My destination this time was the Golden Cliffs trailhead. The trail from there runs up from a parking area to and along the base of the top lava flow.

The Golden Cliffs trailhead is a good choice for exploring the basalt cliffs of North Table Mountain. The West trailhead, on the other hand, provides a more gentle ramp up to the top.

The photos from Boulder Canyon show a course, crystalline rich, granite. Basalt is not that. The difference is that granite and related rocks solidify from magma deep underground. They solidify slowly, allowing recognizable crystals to form from the melt. Basalt, on the other hand, solidifies from lava on the Earth's surface. It solidified quickly so that the molecules don't have time to organize into crystals. The microscopic particles tend to be amorphous like glass. But the chemical constitution of basalt is similar to the larger grained igneous rocks.

Basalt is an example of what's called an aphanitic rock, an igneous rock with a texture in which individual particles are not visible to unaided vision and are often not crystalline. Phanitic rocks, like granite, have easily distinguishable grains.

A few basalt outcrops get most of the attention. The famous ones are the Giant's Causeway in Scotland and the Devil's Tower (also known as Bear Butte) in Wyoming. But basalt outcrops are widely distributed. And, in North America, they're not exclusive to the west. The Palisades along the Hudson River are a good example.

The Table Mountain basalts have the same columnar appearance as the other major outcroppings (it makes them popular with rock climbers). Called "columnar jointing", it's just the way they break as they cool and shrink. You may have noticed that, when an expanse of mud dries out, the material tends to shrink and break up into polygonal shapes. The same thing happens to basalt as it solidifies.

Mud on Little Dry Creek Trail

The Table Mountains are also known as a conservation site for lichens. Golden Parks and Recreation ask that visitors stay to the trails to protect these delicate symbiotic organisms, but, of course, some hikers won't, so there are areas of the mesa that are off limits.

Normally, algae and cyanobacteria can't survive in dry climates. They prefer hanging out on rocks in ponds, but in lichen, they have solved the problem. Lichen is actually two organisms in one. The fungus protects its companion organisms from the arid environment while it obtains nutrients from them. And they have an important place in their environment by being food for both large (for example, reindeer) and small (springtails).

There is a lot packed into the narrow valley between the Table Mountains. A lot of it is the Coors brewery and associated industries but there's also Rocky Mountain Metal Containers, the Colorado Railroad Museum, Colorado highway 58 and West 44th Avenue, and, of course, Clear Creek. Clear Creek, after all, is the reason the gap is there.

The volcano and lava flows are 62 to 64 million years old. Geologically, that's not very old, but they've been around long enough to have been deeply buried by sediments from the Rocky Mountains. Clear Creek, then a powerful river, flowed straight across those sediments and, when it got down to the lava, it kept right on cutting until it cut through all three flows. It's not nearly as big now, but it's still flowing out of the Mountains, through Golden, between the Table Mountains and through Arvada, to join the South Platte River North of Denver.

By the way, Clear Creek is weird in that one of it's tributaries is a river, Fall River. And, of course, Clear Creek was the site of the first gold strike in Colorado and the reason that people started flocking to the future Denver.

After exploring the flank of North Table Mountain, I returned home, thankfully by train with most of the walking downhill.

Now, the sample of sand I collected from the bed of Clear Creek in Golden...

I wasn't really looking for gold, although people do pan for gold on Clear Creek. They might even find some!

My father and I panned for gold in North Georgia for fun. One of our main pieces of equipment was an eye dropper, which we used to suck up the tiny specks of gold we found in creek sand. Those are called, by the initiated, "color" or, more often, "dust".

The Bible is often quoted to say, "gold is where they find it." That's a mistranslation for two reasons. The passage is Job 28:1, "Surely, there is a vein for the silver, and a place for gold where they fine it."(King James version) The second error is that the word is "fine", not "find".

In other words, don't expect to find gold where you're looking for it. You'll find it where it's fined (that is, refined).

Gold is found here...

(in the museum), or here...

(on your electroplated flatware.)

No, I was just sifting through the sand to see what Clear Creek was washing out of the mountains, and I was not disappointed with that, either. It was exactly what I expected.

First, I spread out the sand on a Petri dish and eyeballed it. The grains graded from course chunks of rock around a couple of millimeters to very fine dust. There were some sparkly bits but they turned out to be mica.

Next, I shined and ultraviolet light on the sample and was surprised to see that it actually fluoresced pink! I didn't expect that and I don't know if it was caused by some pollutant or it there is something in the rocks west of town.

Finally, I used my smartphone microscope...

to look at the sample.

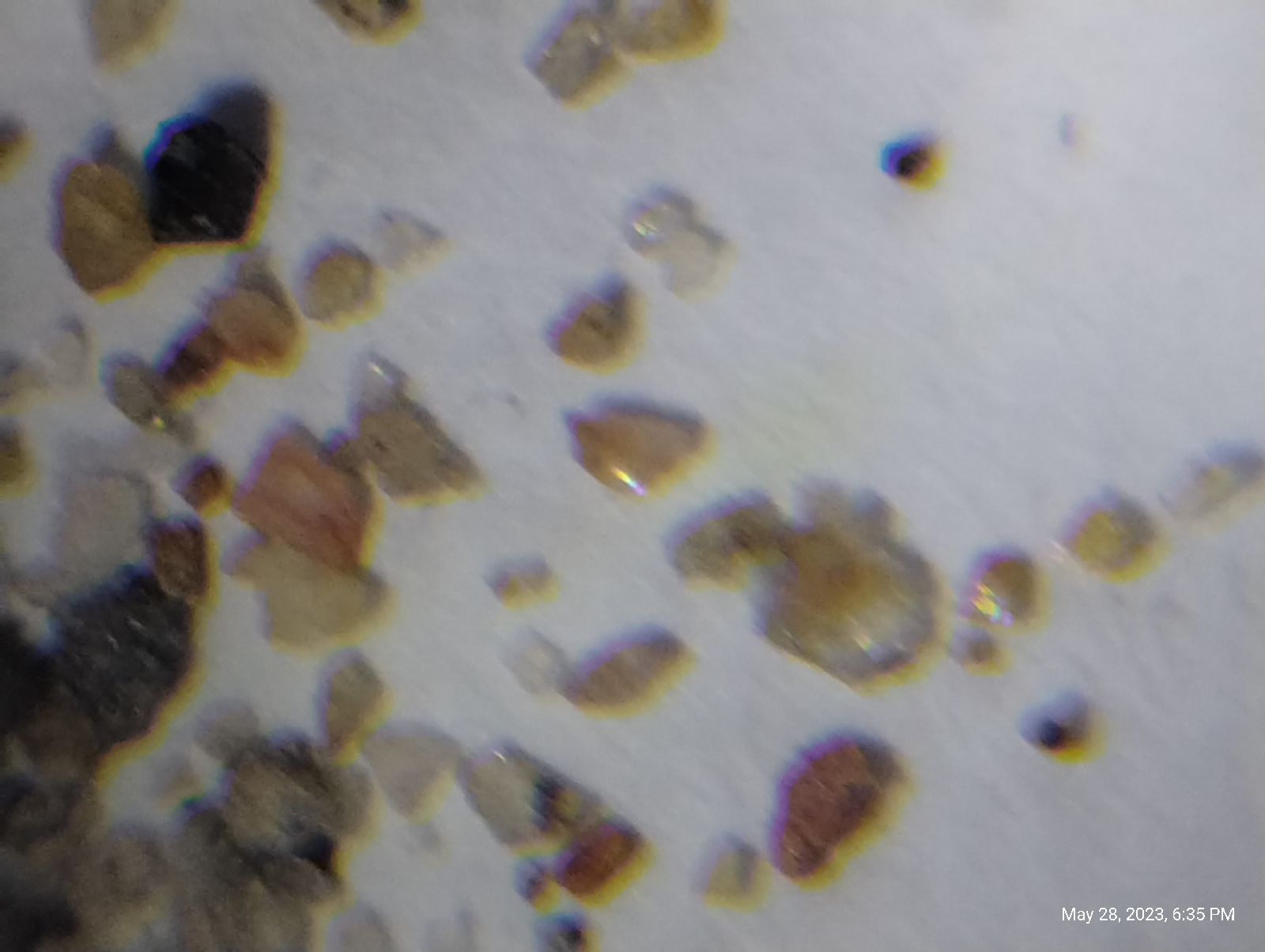

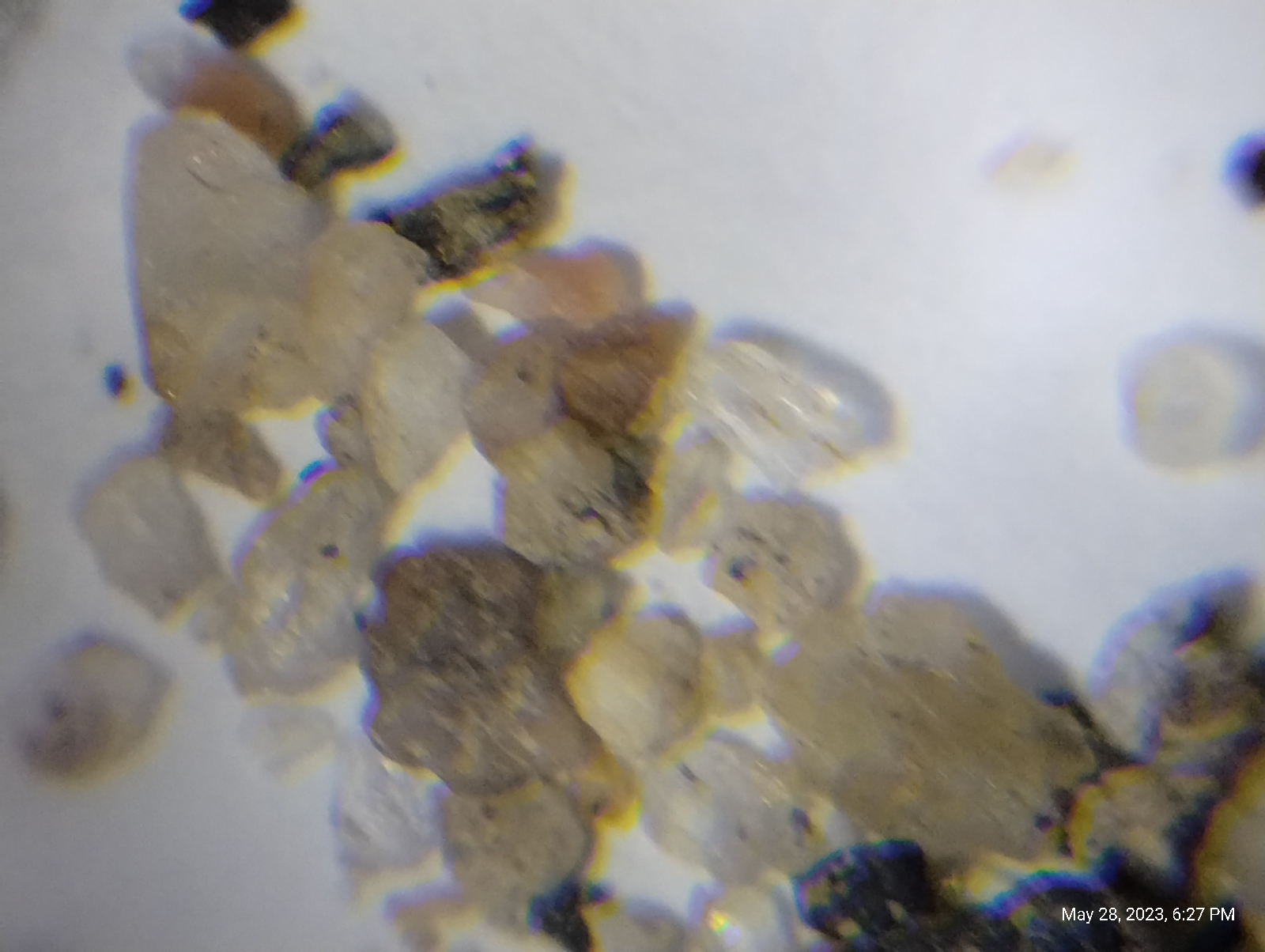

Most of the sand was obviously washed out of the igneous and metamorphic rocks west of the Golden fault.

The chunkier stuff is granite.

Of the individual particles, the clear grains are quartz, the cloudy white or red grains are feldspar (when I caught the light just right, they would shine like moonstone), the flat clear flakes are mica, and the black crystals are mostly hornblende. These are the fundamental rock building minerals of igneous rock. Two others are amphiboles, also dark minerals related to the hornblende, and olivine, which is a constituent in many basaltic rocks.

Here are some more photomicrographs.

Mind you, don't pass up the pleasure of looking at sand under a microscope. As a teenager, I walked down to the creek at the bottom of the hill below my house and collected some sand. When I shined an ultraviolet light on it, some of the grains glowed a brilliant orange. Under the microscope, those grains were tiny octagons of thorite. I also saw zircons and tourmaline crystals.

I'll be revisiting North Table Mountain soon. Stay tuned.

Are there any ancient lava flows near you? Check out the Wikipedia article "List of places with columnar jointed volcanics" for hints.

Pull out a microscope and look at some samples of stream sand from streams near you. What kind of materials do you see? If you have a black light, do they fluoresce? Where did the sand come from - what kind of rock produced it?