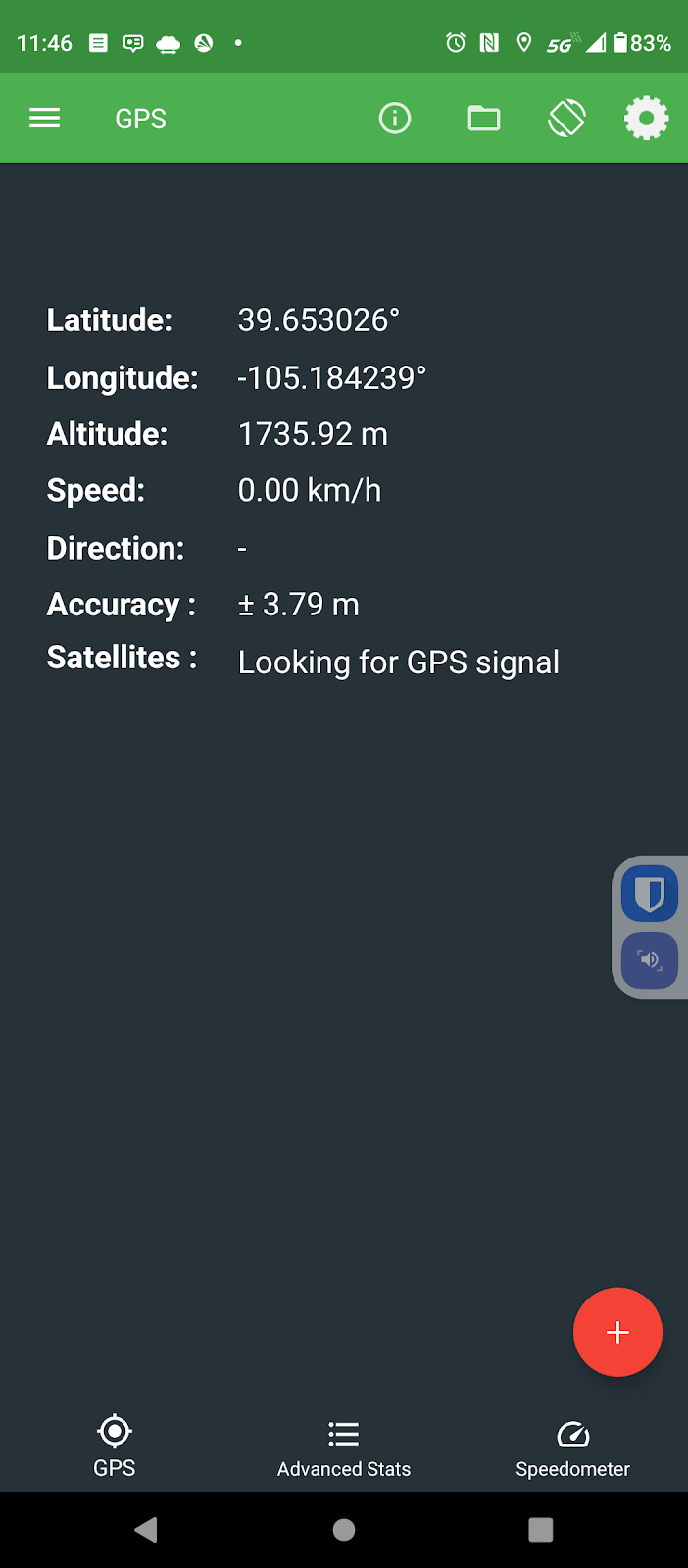

I made these recordings at the Phillips 66 in Morrison at the start of my hike. The weather is holding steady but it's warming up. My sweater has long ago gone into my backpack. The altitude is actually below that of the light rail station at Broadway. That's not surprising since the train station is up above the South Platte River. Morrison is nestled down in the Bear Creek Canyon. I'll be hiking up a lot for awhile.

To the right is the valley cut out by Bear and Mount Vernon Creeks. They flood occasionally so it's a fairly broad area. To the left is the rise to the Rocky Mountains. Here, that would be Mount Morrison and Mount Falcon.

These huge chunks of Fountain formation rock are arkose sandstone. What makes them "arkose" is the large amount of feldspar still in them. What gets eroded out of mountains is usually the constituents of granite - quartz, feldspar, mica, amphiboles, pyroxenes. And small amounts of other stuff. The stuff washed out of the Ancestral Rockies obviously had a lot of dark, iron-bearing minerals such as biotite mica and amphiboles. That's where the red rust comes from when they fall apart chemically. But the feldspar usually goes to clay and quickly gets washed downstream. For there to be feldspar left, the sediments must have been washed out very quickly, deposited close to their source, and buried so that the process of consolidation can begin sooner than later.

There's something else you can see here. Those pockmarks in the rock are called "tafoni" or "honey comb weathering". They're fairly common in desert environments. In really wet places, water just grinds away at rock faces willy-nilly and wears them down large scale. Here, water seeps into the permeable rock and finds weak spots. That's where it starts chemically weathering the stone...in spots.

The sandstone particles are tough because they're cemented together with calcite, but calcite is soluble in acids, and dew and occasional rain is weakly acid from the carbon dioxide it has dissolved. That's how caves form in limestone, which is primarily calcite. In sandstone, the quartz particles (sand) just fall out to form these little holes and horizontal and vertical joints.

The wind and moisture isn't in any hurry to do widespread damage so they can be artistic, carving out these spectacular rock sculptures.

There are a couple of streams in the neighborhood. Bear Creek is a picturesque mountain stream draining the area around Mount Blue Sky. It comes in crashing in from the west having cut out it's canyon. Mount Vernon Creek is a smaller, lazier stream that pours in from the north skirting the edge of the hogback. Most of the streams in Red Rocks Park are like the one shown above...dry until it rains. They're called "draws". This landscape would fit right in with any John Ford western.

Typically, the Fountain formation show up as "standing stones". They look like they were arranged by some giant child marching off into the horizon. Now you know why. They're the shell of the Rocky Mountains, cracked open as the present Rockies were born. Most of the red sandstone on top have long ago been weathered to nothing but there are still some places in the mountains where there are remnants such as Red Rocks Campground, near Woodland Park, west of Pike's Peak.

This is a view south on the Trading Post Trail that runs from a parking lot near the South Entrance to the park to the Trading Post/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Museum at the base of the amphitheatre.

The lower part of the trail is loose rock and sand deposited by present streams, mostly flooding by Bear Creek, but near the amphitheatre, the flat rock is Fountain formation, giving the hiker an opportunity to see Red Rocks closeup. These ripples are cause by the same weathering that creaked the tefoni in the standing stones.

That's part of the amphitheatre peeking out from behind the little tree. I followed the Trading Post Trail up and around to the grueling stairs up the side of Red Rocks Amphitheatre called the Funicular Trail, which leads to the upper parking lot.

When Red Rocks Park was first built, there was a funicular railroad that carried visitors to the summit of Mount Morrison for a grand view of ...well, everything....mountains, canyon, plains, Red Rocks. To get up there now, you have to hike, but the stairs will get you part way if your knees and lungs hold out.

At the upper parking lot is this...

This is the mystery I promised you at the end of the last blog. At the breadth of a finger is a gap of over a billion years!

It's called the Great Unconformity. The red Rocks on top are the 300 million year old Fountain formation. They sit directly on top of 1.7 billion years old rock of the Idaho Springs formation. What happened in between?

The grayish rock at the bottom is metamorphic gneiss and it's older than the land that would become Colorado. Over a billion years ago a chain of volcanic island crashed into the North American plate and stuck. Rocks like this were lifted with the rest of the Rockies during the Laramie orogeny to become the core of the mountains.

But what happened to the geologic history of over a billion years? Nobody knows for sure but the most popular answer I find reading about the Great Unconformity is erosion. Something scraped all that accumulated debris off the core rock 400 million years ago.

Of course, the erosion that formed the Fountain formation razed the Ancestral Rockies to level plains. The sediments above the metamorphic and igneous core of those ancient hills simply washed to the sea. As the hills came down and their slopes leveled out, the sediments were deposited closer and closer (gentler slopes meant slower water currents) until the erosion met granite and gneiss and the sand was laid down right there in what would become Red Rocks Park.

But some geologists find even that to be a weak explanation for the elimination of a billion years of strata.

A tantalizing theory is that the great eraser, glaciers, did it. About that time is when some geologists speculate that Ice covered the Earth, a time they call "the snowball Earth."

West Alameda Parkway begins in Aurora (East Denver Metro) at the Buckley Space Force Base, runs through Denver (one of my favorite shopping areas is around Alameda and Broadway) and ends at the top parking lot of Red Rocks Amphitheatre. In fact, Dinosaur Ridge is a closed off section of Alameda. It passes through a tunnel in a big chunk of the Fountain formation and, not long after, the Plains View Road splits off to the left and leads to the Geological Overlook Trailhead. That looked inviting so I took the bait. It wasn't long before I realized that, if I wanted to make it to Golden before night, I needed to turn back, but before I did, I took a few shorts from a high point (the trail climbs up about a third the distance to the summit of Mount Morrison.) The photo above is one of them.

The two hills in the distance is the mouth of Bear Creek Canyon and just beyond is Bear Creek Lake and Mount Carbon.

This is a view back down to the amphitheatre and Mount Falcon beyond.

Here's some more of that chemical weathering. It gets pretty extensive in some of the areas in Red Rock Park.

A little further north on Alameda Parkway I find the other end of the Geological Overlook Trail and realize that the overlook itself is just off the road, so I take another picture. There's a big sign there that tells you what you're looking at but it was crowded and I try not to get recognizable pictures of people without their permission, so I just got a panorama from the side.

A little more roadwork brought me to Dinosaur Ridge, and that will be the main subject of the next section of Anatomy of a Mountain Range.

No comments:

Post a Comment