Back at Golden.

The view from the Jefferson County Government Center gives me a preview of what I'm in for. There was a misty rain which I was afraid the sun would burn off as the day progressed (thankfully, it didn't ). That's North Table Mountain in the distance

The last time, I hiked through Golden to the Golden Cliffs trailhead and looked at the basalt columns from the base. This time, I intended to go to the top, so I hired a Lyft to take me from the train station to the west trailhead.

Some information about North Table Mountain. It's a mesa (flat top mountain..."mesa" is Spanish for "table" so it amuses me how many "table mesas" there are.) The summit is 1,998 meters (6,555 feet) above sea level. It's prominence is 177 meters (571 feet). Prominence is height from base to summit. The west trailhead is 4.8 miles from Golden Station.

It's isolation is 2.18 miles (that's the distance from it's summit to the nearest place of equal elevation). It's not actually a Rocky Mountain. Like nearby South Table Mountain, Green Mountain, Grand Mesa, and Mount Carbon, it is an erosion feature of the High Plains. Except for the lava flows, it is all sedimentary rock.

The first recorded ascent was in the 1840s by Black Kettle, a Cheyenne chief, and his tribe.

This hill, featured in the last Volcano blog, is not Rolston Dike... it's not even a dike. Rolston Dike is another couple of miles down the road. I'll include a picture from a distance later. This is what's left of the Dakota hogback here in Golden. A little to the south, it is just a hilly terrain in town. It's also where a lot of dinosaur tracks have been found. The origin of Dakota sandstone is beachfront sand from 100 to 113 million years ago.

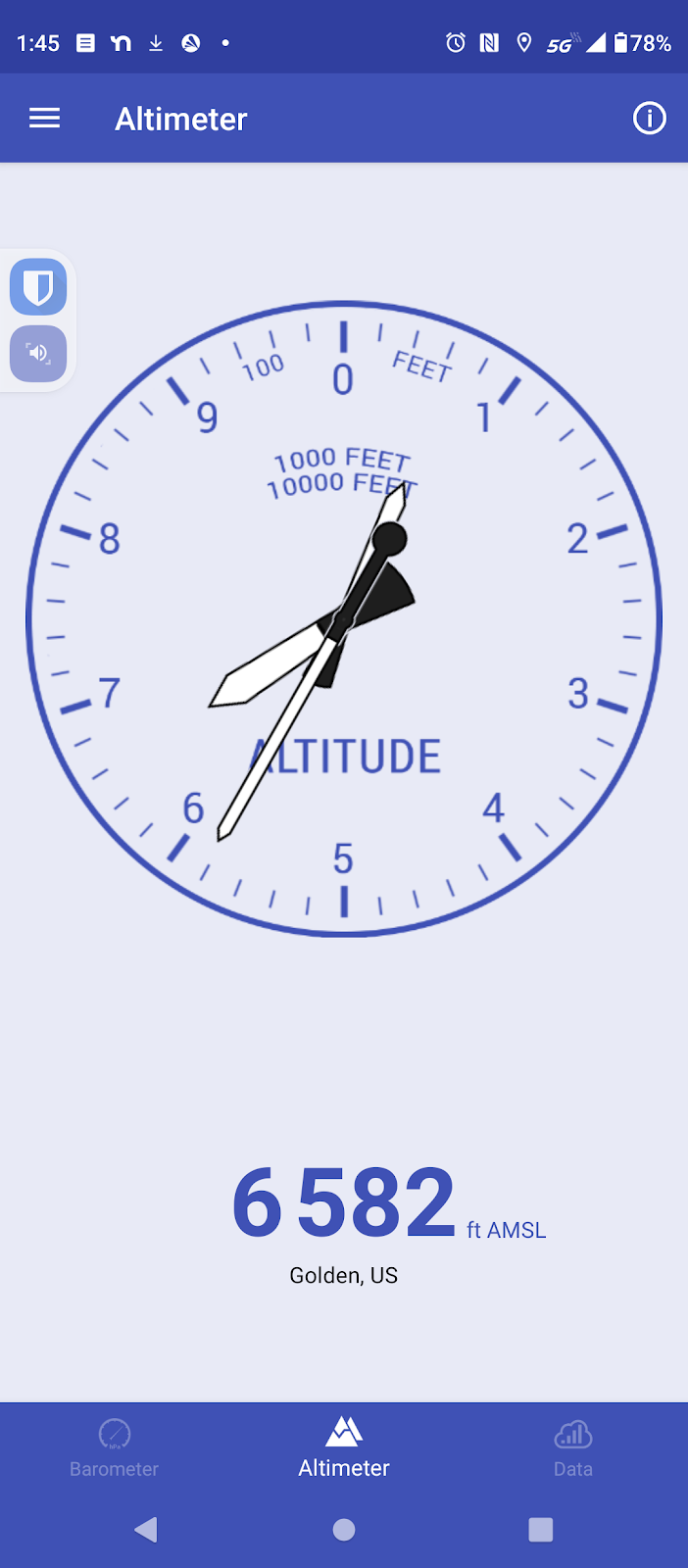

I took some instrument readings at the trailhead.

The average magnetic field strength for the Earth's magnetic field is around 25 to 65 microteslas. This reading is pretty high but there are houses and power lines nearby.

The Physics Pro app barometric pressure agrees with the dial reading of the Trail Sense app. The digital readout on the Trail Sense app differs because I didn't give it a chance to "catch up" to the current reading. I'll go with the 1014 hectopascals.

Temperature, wind speed, visibility, and humidity are taken from a local weather station, and there might be more than one. The barometer and altimeter readings are taken from the phone's sensors and are more reliable.

I took these primarily to compare to the readings at the top of the mesa

The trail from the west trailhead is a service road leading to an old basalt quarry. This is a view back down the mountain. There are neighborhoods up the flanks of both Table Mountains.

As for the instrument readings at the top...

The barometer readings were spiky, which was to be expected from the way the winds were gusting on top. Overall, barometric pressure had dropped. That would be expected for an elevation increase, but not this much. There was a front moving through.

Magnetic field strength was also much less and much more comparable to Earth's magnetic field strength. There were power lines on the mesa but they where some distance away.

This indicates that the distance from the trail head to the top of the mesa was 471 feet. That's not the prominence since the trail head starts at a distance (it looks like about 100 feet) above the base of the mountain.

The altimeter reading is based on the barometric pressure which decreased with altitude. Of course, barometric pressure also changes with the weather so altimeters must include compensations for that. The compensations aren't perfect so there is a little variance in the altitude readings.

Humidity was increasing so, with decreasing pressure, I could expect some rain, and I got it later but it wasn't bad...just a mist to cool things off. I was thankful for that

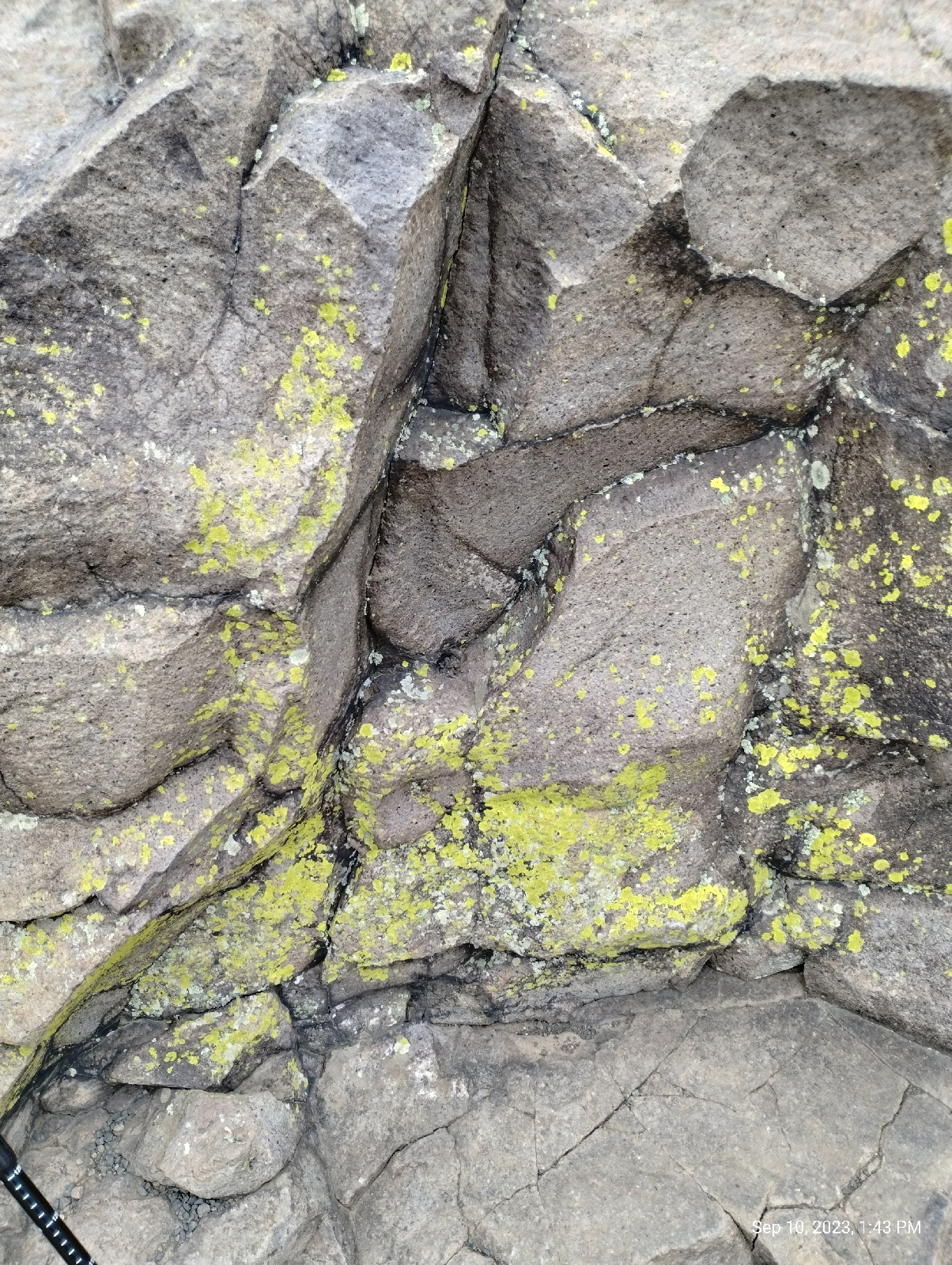

The quarry at the top displays the typical jointing of basalt seen also at more well known locations like the Giant's Causeway in Scotland and the Devil's Tower (Bear Butte) in Wyoming. The stockade-like appearance is caused by shrinkage that occured as the lava solidified. It has been intensified by weathering. The basalt contains feldspar which weather to clay and olivine which breaks down to serpentine. Here are some boulders of basalt along the trail. Notice the absence of coarse detail. The rock is almost homogeneous.

Basalt is used as a decorative building stone and has been carved into works of art.

Both Table Mountains are popular climbing areas. On North Table Mountain, Golden Cliffs and four quarries have been extensively mapped and bolted for climbing trails.

There is a lot of vegetation on North Table Mountain but very little of it grows above waist height. The soil isn't deep. A surprising amount of wildlife, and not just birds and insects, call the place home. I didn't see any large mammals but the Golden Parks and Recreation brochure says that prairie dogs, deer, bear, coyotes, and other animals live there. It also says that bighorn sheep pass through but don't live there. There are also rattlesnakes so, be vigilant.

The mountain is home, also, to conservation studies and other researchers. There was currently a rattlesnake study going on but I didn't notice researchers present at the time.

It looks like a big rock pile (and it is, but it's all natural). Lichen Peak is the summit of North Table Mountain at 1998 meters (6555 feet) (actually, the highest point is at a surveyor's marker at the other end of the mesa which reads 1999 meters (6558 feet) ). Given my altimeter reading, that would make Lichen Peak 30 feet high from it's base on the mesa.

Note, if you ever visit, I couldn't get a satellite reading to check my barometer against GPS. There are a lot of dead zones in and near the Rockies.

This is what the top of those basalt columns look like.

There are four lava flows discernable on North Table Mountain (two on South Table Mountain). The lowest one, and, thus oldest, is around 6250' elevation. I didn't see outcroppings of that on my hike. The oldest flow is about 64 million years old and it can be seen about halfway up North Table Mountain. I keep reading that the oldest flow is monzontite and the younger two are latite, but I don't get it.

In the first place, I checked back with the original reference (Van Horn, R. 1957. Bedrock geology of the Golden Quadrangle, Colorado. U.S. Geological Survey, Map GQ-103.) and it calls all the flows latite. The big problem is that lava doesn't produce monzontite since monzontite is a crystalline, intrusive rock and lava cools too quickly to form crystalline rocks. The error may be caused by the fact that there is a monzontite intrusion on North Table Mountain.

There are different kinds of rock formed by solidifying lava. Latite is a feldspar rich, quartz poor apheritic to porphyritic rock. That describes the lava flows on North Table Mountain pretty well.

The latest flows are both on top and are about 62 million years old. They are sometimes described (as in the Rockd app) as shoshonite. You can see the two flows in the photograph above. The material capped by the flows (and, thus, protected from erosion) is the same Dawson formation that underlies most of the Denver area.

The oldest flows are channel flows. The vents, between Rolston Dike and North Table Mountain, were small and didn't produce as much lava as the later flows, so the lava ran along depressions in the landscape. The later flows from the Rolston Dike plug blanketed the area.

A fairly recent and informative study was published in 2008 by the United States Geological Survey as Scientific Investigation Report 2006-5242 (Table Mountain Shoshonite Porphyry Lava Flows and their Vents, Golden, Colorado by Harald Drewes).

Lichens are one of the focuses of conservation efforts on North Table Mountain.

A lichen isn't a lifeform. It's a symbiosis of two, an algae and a fungus. The algae produces nourishment for the fungus and the fungus provides a protective environment for the algae (algae is usually, well, pond scum, and doesn't generally thrive in dry environments.) The arrangement is effective and lichens can thrive is very harsh surroundings, like the Arctic. They are popular food among reindeer. What they don't deal with very well is trampling. They can't do "urban" very well.

There are several springs on the Table Mountains. As the Rockies eroded while the plateau was rising and afterwards, they literally buried themselves. The uplift has occurred in three phases and the early Rockies were little more than hills so it isn't that surprising that they were completely buried in sediments. Eventually, rain, snow and wind carried the debris eastwards to fill in the depression called the Denver Basin. After the Golden volcano erupted, it were also buried. There were at least four eruptions, the first two were small and the lava was just enough to follow stream valleys and harden into basalt fingers pointing eastwards. The two later eruptions were much bigger and covered a broad area and they were also buried by sediments. These eruptions were more like Hawaiian eruptions and not like Mount St. Helens....they were not explosive.

Lookout Mountain, the tall mountain that looms over Golden was completely buried, as was the lava flows and the volcano, but the streams in the area were working, carving away at the fairly soft sandstones and mudstones, until they reached the hard basalt, then they changed course to flow around it, forming the broad valley in which Golden is situated today. But only Clear Creek was big enough and carried enough energy out of it's canyon to cut into the basalt, so it split the flow in two forming the two mesas.

The sediments in the basin and sandwiched between the lava flows are active aquifers. Rain and snow melt soaks down into the permeable rocks and expand in the deeper heats of the Earth's crust, creating a pressure that pushes them back to the surface along faults. The result is springs, and there are several on the mesa creating swampy areas and small ponds. If you look at a topographical map of the mountains, you see gulleys running down the sides. They're usually dry but rain swells the springs and the water runs off the sides in these gulleys.

The vegetation on top is short with a few shrub sized plants dotting the landscape. They're bonsais. They get plenty of water but the topsoil isn't very deep so plants have little room to grow, so they stay small.

That's probably what's left of the volcano...not much. The long lake, called unimaginatively "Long Lake" is backed by a low ridge. On the other side is another long lake, that one man-made, called Rolston Reservoir. The ridge is a plug of monzontite called Rolston Dike. It's considerably deeper than it is wide. Monzontite is an intrusive rock that was deep enough to have cooled slowly. Crystals formed as the molten rock solidified. Monzontite is fairly quartz poor, unlike granite and granodiorite, having less than 5% quartz. It is very similar in chemical composition to the basalt on the Table Mountains.

It is very likely the source of the top two lava flows. There are a few smaller monzontite plugs between Rolston Dike and North Table Mountain that were probably the source of the two lower flows. Time, erosion, and quarrying have brought the volcano down to it's current humble level. I may visit the dike later if the trip doesn't involve trespassing.

The trip down North Table Mountain follows another service road, this one leading to the radio tower on top. There's the Dakota hogback again backed by the Front Range. The trail winds it's way back to the North trailhead where I began my ascent.

This inhabitant of the mountain died there. I don't know what it was. The skull was absent, probably taken as a trophy. It was too small to be a full grown deer.

I took a Lyft from the train station to North Table Mountain trailhead but decided to walk back. The day was cool and I was in pretty good shape. Nonetheless Avenue Trail follows Colorado Highway 9 from the trailhead directly to Golden Station. A lot of the way is down hill but, once it crosses Clear Creek, it's uphill all the way. It's an interesting urban trail with side trails into fossil quarries and trackways. I didn't dawdle.

It's always uplifting to see the rotunda of the Jefferson County Government Center in the distance. The train station is right next door. I felt as eroded and worn as Golden Volcano as I boarded the train back home.

I looked forward to the two train rides to my home station...not so much the mile and a half trek from Arapahoe Station home

Not many of us live near active volcanoes like the denizens of the Ring of Fire around the Pacific Ocean, Hawaii, or Iceland, but mountain building involves volcanoes and if your live near a mountain range, there are probably the remnants of these "fossil volcanoes" within a day's drive. They make for fascinating hikes.